FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES

Johannes Gutenberg – Wikipedia

Described as the “man of the millennium”, Gutenberg is often cited as among the most influential figures in human history. Gutenberg died penniless on 3 February 1468.

“Printing is the ultimate gift of God and the greatest one.” — Martin Luther

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (German pronunciation: [joˈhanəs ˈɡɛnsflaɪ̯ʃ t͜sʊʁ ˈlaːdn̩ t͜sʊm ˈɡuːtn̩bɛʁk]; English: /ˈɡuːtənbɜːrɡ/; c. 1393–1406 – 3 February 1468) was a German inventor and craftsman who introduced letterpress printing to Europe with his movable-type printing press. Though not the first of its kind, earlier designs were restricted to East Asia, and Gutenberg’s version was the first to spread across the world.[2] His work led to an information revolution and the unprecedented mass-spread of literature throughout Europe. It also had a direct impact on the development of the Renaissance, Reformation and humanist movement, as all of which have been described as “unthinkable” without Gutenberg’s invention.[3]

His many contributions to printing include the invention of a process for mass-producing movable type; the use of oil-based ink for printing books;[4] adjustable molds;[5] mechanical movable type; and the use of a wooden printing press similar to the agricultural screw presses of the period.[6] Gutenberg’s method for making type is traditionally considered to have included a type metal alloy and a hand mould for casting type. The alloy was a mixture of lead, tin, and antimony that melted at a relatively low temperature for faster and more economical casting, cast well, and created a durable type.[7] His major work, the Gutenberg Bible, was the first printed version of the Bible and has been acclaimed for its high aesthetic and technical quality.

Described as the “man of the millennium”, Gutenberg is often cited as among the most influential figures in human history. He has been commemorated around the world and is a frequent namesake. To celebrate the 400th anniversary of his death in 1900, the Gutenberg Museum was founded in his hometown of Mainz.

The Printing Revolution in Renaissance Europe – World History

FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES

The arrival in Europe of the printing press with moveable metal type in the 1450s CE was an event which had enormous and long-lasting consequences. The German printer Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1398-1468 CE) is widely credited with the innovation and he famously printed an edition of the Bible in 1456 CE. Beginning with religious works and textbooks, soon presses were churning out all manner of texts from Reformation pamphlets to romantic novels. The number of books greatly increased, their cost diminished and so more people read than ever before. Ideas were transmitted across Europe as scholars published their own works, commentaries on ancient texts, and criticism of each other. Authorities like the Catholic Church took exception to some books and censored or even burned them, but the public’s attitude to books and reading was by then already changed forever.

The impact of the printing press in Europe included:

- A huge increase in the volume of books produced compared to handmade works.

- An increase in the access to books in terms of physical availability and lower cost.

- More authors were published, including unknown writers.

- A successful author could now earn a living solely through writing.

- An increase in the use and standardisation of the vernacular as opposed to Latin in books.

- An increase in literacy rates.

- The rapid spread of ideas concerning religion, history, science, poetry, art, and daily life.

- An increase in the accuracy of ancient canonical texts.

- Movements could now be easily organised by leaders who had no physical contact with their followers.

- The creation of public libraries.

- The censorship of books by concerned authorities.

Johannes Gutenberg

The invention of the movable metal type printer in Europe is usually credited to the German printer Johannes Gutenberg. However, there are other claims, notably the Dutch printer Laurens Janszoon Coster (c. 1370-1440 CE) and two other early German printers, Johann Fust (c. 1400-1465 CE) and his son-in-law Peter Schöffer (c. 1425-1502 CE). There is, too, evidence that movable metal type printers had already been invented in Korea in 1234 CE in the Goryeo Kingdom (918-1392 CE). Chinese Buddhist scholars also printed religious works using moveable type presses; the earliest ones used woodblocks during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE). Whether the idea of moveable type presses spread via merchants and travellers from Asia to Europe or if the invention by Gutenberg was spontaneous is still a point of debate amongst scholars. In any case, like most technologies in history, the invention likely sprang from a cumulation of elements, ideas, and necessity involving multiple individuals across time and space.

Gutenberg began his printing experiments sometime in the 1440s CE, and he was able to establish his printing firm in Mainz in 1450 CE. Gutenberg’s printer used Gothic script letters. Each letter was made on a metal block by engraving it into the base of a copper mould and then filling the mould with molten metal. Individual blocks were arranged in a frame to create a text and then covered in a viscous ink. Next, a sheet of paper, at that time made from old linen and rags, was mechanically pressed onto the metal blocks. Gutenberg’s success in putting all these elements together is indicated by his printed edition of the Latin Bible in 1456 CE.

The new type of presses soon appeared elsewhere, notably with two Germans, Arnold Pannartz (d. 1476 CE) and Conrad Sweynheym (aka Schweinheim, d. 1477 CE). This pair established their printing press in 1465 CE in the Benedictine monastery of Subiaco. It was the first such press in Italy. Pannartz and Sweynheym moved their operation to Rome in 1467 CE and then Venice in 1469 CE, which already had a long experience of printing such things as playing cards. There were still some problems such as the lack of quality compared to handmade books and the drab presentation in respect to beautifully colour-illustrated manuscripts. Also, there were sometimes errors seen in the early printed editions and these mistakes were often then repeated in later editions. However, the revolution into how and what people read had well and truly begun.

Printed Matter

There was already a well-established demand for books from the clergy and the many new universities and grammar schools which had sprung up across Europe in the late medieval period. Indeed, traditional book-makers had struggled to keep up with demand in the first half of the 15th century CE, with quality often being compromised. This demand for religious material, in particular, was one of the main driving forces behind the invention of the printing press. Scholars had access to manuscripts in private and monastic libraries, but even they struggled to find copies of many texts, and they often had to travel far and wide to get access to them. Consequently, religious works and textbooks for study would dominate the printing presses throughout the 15th century CE. It is important to remember, though, that handmade books continued to be produced long after the printing press had arrived and, as with many new technologies, there were people still convinced that the flimsy printed book would never really catch on.

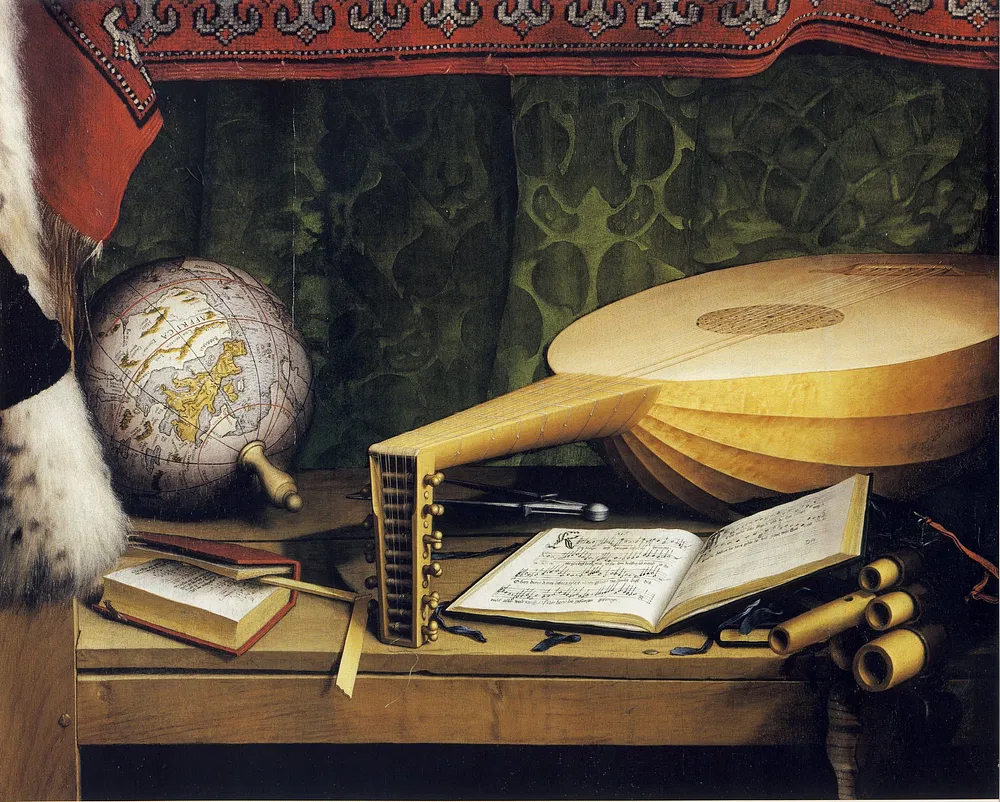

The availability of things to read for people in general massively increased thanks to printing. Previously, the opportunity to read anything at all was rather limited. Ordinary folks often had little more than church notice boards to read. The printing press offered all sorts of new and exciting possibilities such as informative pamphlets, travel guides, collections of poems, romantic novels, histories of art and architecture, cooking and medicinal recipes, maps, posters, cartoons, and sheet music. Books were still not as cheap as today in terms of price compared to income, but they were only around one-eighth of the price of a handmade book. With printing matter being varied and affordable, people who could not previously do so now had a real motive to read and so literacy rates increased. Further, printed books were themselves a catalyst for literacy as works were produced that could be used to teach people how to read and write. At the end of the medieval period still only 1 in 10 people at most were able to read extended texts. With the arrival of the printing press, this figure would never be as low again.

The Spread of Information

Soon, a new boost to the quantity of printed material came with the rise of the humanist movement and its interest in reviving literature from ancient Greece and Rome. Two printers, in particular, profited from this new demand: the Frenchman Nicholas Jensen (1420-1480 CE) and the Italian Aldus Manutius (c. 1452-1515 CE). Jensen innovated with new typefaces in his printing shop in Venice, including the easy-to-read roman type (littera antiqua/lettera antica) and a Greek font which imitated manuscript texts. Jensen printed over 70 books in the 1470s CE, including Pliny’s Natural History in 1472 CE. Some of these books had illustrations and decorations added by hand to recapture the quality of older, entirely handmade books.

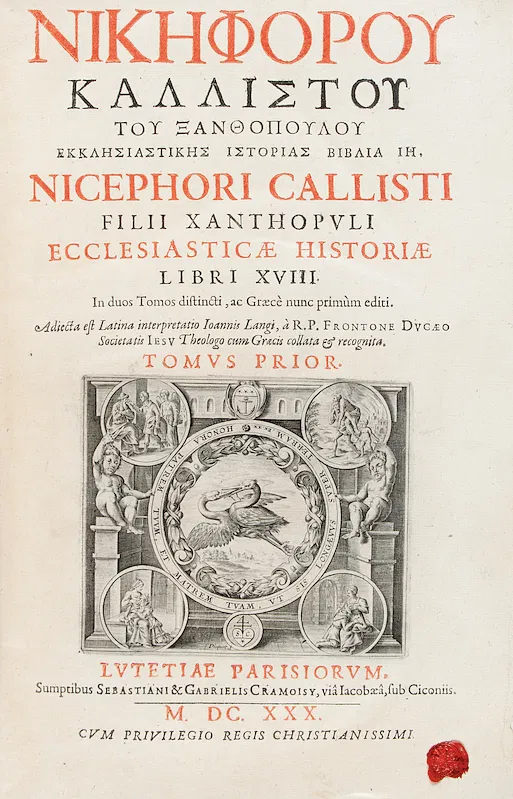

Meanwhile Manutius, also operating in Venice, specialised in smaller pocket editions of classical texts and contemporary humanist authors. By 1515 CE, all major classical writers were available in print, most in multiple editions and many as collections of complete works. In addition, printed classical texts with identical multiple copies in the hands of scholars across Europe could now be easily checked for accuracy against source manuscripts. Handmade books had often perpetuated errors, omissions, and additions made by individual copyists over centuries, but now, gradually, definitive editions of classical works could be realised which were as close as possible to the ancient original. In short, printed works became both the cause and fruit of an international collective scholarship, a phenomenon which would reap rewards in many other areas from astronomy to zoology.

There was, too, a drive to print more books thanks to the Reformists who began to question the Catholic Church’s interpretation of the Bible and its stranglehold on how Christians should think and worship. The Bible was one of the priorities to have translated into vernacular languages, for example German (1466 CE), Italian (1471 CE), Dutch (1477 CE), Catalan (1478 CE), and Czech (1488 CE). Reformists and humanists wrote commentaries on primary sources and argued with each other in print, thereby establishing an invisible web of knowledge and scholarship across Europe. Even the letters written between these scholars were published. As religious and academic issues raged, so the debating scholars fuelled the production of yet more printed works in a perpetuating cycle of the printed word. Ordinary folks, too, were roused by arguments presented in printed materials so that groups of like-minded individuals were able to quickly spread their ideas and organise mass movements across multiple cities such as during the German Peasants’ War of 1525 CE.

There were, too, plenty of works for non-scholars. As more people began to read, so more collections of poems, novellas, and romances were printed, establishing Europe-wide trends in literature. These secular works were often written in the vernacular and not the Latin scholars then preferred. Finally, many books included a number of woodcut engravings to illustrate the text. Collections of fine prints of famous paintings, sculptures, and frescoes became very popular and helped to spread ideas in art across countries so that a painter like Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528 CE) in Germany could see what Raphael (1483-1520 CE) was up to in Italy.

A Booming Industry

As a consequence of all this demand, those printers who had survived the difficult early years were now booming. Cities across Europe began to boast their own printing firms. Places like Venice, Paris, Rome, Florence, Milan, Basel, Frankfurt, and Valencia all had well-established trade connections (important to import paper and export the final product) and so they became excellent places to produce printed material. Some of these publishers are still around today, notably the Italian company Giunti. Each year, major cities were producing 2-3,000 books every year. In the first decade of the 1500s CE, it is estimated 2 million books were printed in Europe, up to 20 million by 1550 CE, and around 150 million by 1600 CE. There were over half a million works by the Reformist Martin Luther (1483-1546 CE) printed between 1516 and 1521 CE alone. Into the 16th century CE, even small towns now had their own printing press.

Besides established authors, many publishers helped new authors (men and women) print their works at a loss in the hope that a lucrative reprint run would finally bring in a profit. The typical print run for a first edition was around 1,000 copies although this depended on the quality of the book as editions ranged from rough paper pocket-sizes to large vellum (calfskin) folio editions for the connoisseur. The smaller size of most printed books compared to handmade volumes meant that habits of reading and storing books changed. Now a desk was no longer required to support large books and one could read anywhere. Similarly, books were no longer kept horizontally in chests but stacked vertically on shelves. There were even odd inventions like the book wheel on which several books could be kept open and easily consulted simultaneously by turning the wheel, especially useful for research scholars. As readers accumulated their books and built up impressive private collections, so many bequeathed these to their city when they died. In this way, within 50 years of the printing press’ invention, public libraries were formed across Europe.

Printed works became so common, they helped enormously to establish the reputations, fame and wealth of certain writers. The Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus (c. 1469-1536 CE) is perhaps the best example, one of the first authors to make a living solely through writing books. There were, though, some threats to authors and printers. One of the biggest problems was copyright infringement because it was next to impossible to control what went on beyond a particular city. Many books were copied and reprinted without permission, and the quality of these rip-offs was not always very good.

Censorship & Printing the Wrong Books

All of these developments were not welcomed by all people. The Catholic Church was particularly concerned that some printed books might lead people to doubt their local clergy or even turn away from the Church. Some of these works had been first released in manuscript form a century or more earlier but they were now enjoying a new wave of popularity thanks to printed versions. Some new works were more overtly dangerous such as those written by Reformists. For this reason, in the mid-16th century CE, lists were compiled of forbidden books. The first such list, the 1538 CE Italian Index of Prohibited Books, was issued by the Senate of Milan. The Papacy and other cities and states across Europe soon followed the practice where certain books could not be printed, read, or owned, and anyone caught doing so was, at least in theory, punished. Further measures included checking texts before they were published and the more careful issuing of licenses to printers.

Institutionalised censorship, then, became a lasting reality of publishing from the mid-16th century CE as rulers and authorities finally began to wake up to the influence of printed matter. Authorities banned certain works or even anything written by a particular author. The De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, 1543 CE) by the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543 CE) was added to the forbidden list for putting the Sun at the centre of the solar system instead of the Earth. The Decameron (c. 1353 CE) by the Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375 CE) was added to the list because of its vulgarity. The works of Niccolò Machiavelli were added for his political cynicism.

The worst works singled out for censorship were burned in public displays, the most infamous being the bonfire of the ‘vanities’ orchestrated by Girolamo Savonarola, a Florentine Dominican friar, in 1497 CE. On the other hand, some works were eventually allowed to be published (or republished) if they were appropriately edited or had offending parts removed. Most printers did not fight this development but simply printed more of what the authorities approved of. There was certainly, though, an underground market for banned books.

Many intellectuals, too, were equally dismayed at the availability of certain texts to a wide and indiscriminate audience. The Divine Comedy (c. 1319 CE) by the Italian poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321 CE) was thought by some to contain certain moral, philosophical, and scientific ideas too dangerous for non-scholars to contemplate. Similarly, some scholars lamented the challenge the vernacular language was posing to Latin, what they considered the proper form of the written word. The tide had turned already, though, and local vernaculars became more standardised thanks to editors trying to make their material more comprehensible to the greatest number of readers. An improved use of punctuation was another consequence of the printed word.

Another delicate area was instruction books. Printers produced trade manuals on anything from architecture to pottery and here again, some people, especially guilds, were not so happy that detailed information on skilled crafts – the original ‘trade secrets’ – could be revealed to anyone with the money to buy a book. Finally, the printed word sometimes posed a challenge to oral traditions such as the professionals who recited songs, lyrical poetry, and folk tales. On the other hand, many authors and scholars transcribed these traditions into the printed form and so preserved them for future generations up to the present day and beyond.

7 Ways the Printing Press Changed the World

FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES

Knowledge is power, as the saying goes, and the invention of the mechanical movable type printing press helped disseminate knowledge wider and faster than ever before.

German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg is credited with inventing the printing press around 1436, although he was far from the first to automate the book-printing process. Woodblock printing in China dates back to the 9th century and Korean bookmakers were printing with moveable metal type a century before Gutenberg.

But most historians believe Gutenberg’s adaptation, which employed a screw-type wine press to squeeze down evenly on the inked metal type, was the key to unlocking the modern age. With the newfound ability to inexpensively mass-produce books on every imaginable topic, revolutionary ideas and priceless ancient knowledge were placed in the hands of every literate European, whose numbers doubled every century.

Here are just some of the ways the printing press helped pull Europe out of the Middle Ages and accelerate human progress.

- 1. A Global News Network Was Launched

- 2. The Renaissance Kicked Into High Gear

- 3. Martin Luther Becomes the First Best-Selling Author

- 4. Printing Powers the Scientific Revolution

- 5. Fringe Voices Get a Platform

- 6. From Public Opinion to Popular Revolution

- 7. Machines ‘Steal Jobs’ From Workers

1. A Global News Network Was Launched

Johannes Gutenberg’s first printing press.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Gutenberg didn’t live to see the immense impact of his invention. His greatest accomplishment was the first print run of the Bible in Latin, which took three years to print around 200 copies, a miraculously speedy achievement in the day of hand-copied manuscripts.

But as historian Ada Palmer explains, Gutenberg’s invention wasn’t profitable until there was a distribution network for books. Palmer, a professor of early modern European history at the University of Chicago, compares early printed books like the Gutenberg Bible to how e-books struggled to find a market before Amazon introduced the Kindle.

“Congratulations, you’ve printed 200 copies of the Bible; there are about three people in your town who can read the Bible in Latin,” says Palmer. “What are you going to do with the other 197 copies?”

Gutenberg died penniless, his presses impounded by his creditors. Other German printers fled for greener pastures, eventually arriving in Venice, which was the central shipping hub of the Mediterranean in the late 15th century.

“If you printed 200 copies of a book in Venice, you could sell five to the captain of each ship leaving port,” says Palmer, which created the first mass-distribution mechanism for printed books.

The ships left Venice carrying religious texts and literature, but also breaking news from across the known world. Printers in Venice sold four-page news pamphlets to sailors, and when their ships arrived in distant ports, local printers would copy the pamphlets and hand them off to riders who would race them off to dozens of towns.

Since literacy rates were still very low in the 1490s, locals would gather at the pub to hear a paid reader recite the latest news, which was everything from bawdy scandals to war reports.

“This radically changed the consumption of news,” says Palmer. “It made it normal to go check the news every day.”

2. The Renaissance Kicked Into High Gear

Sketch of a printing press taken from a notebook by Leonardo Da Vinci.

SSPL/Getty Images

The Italian Renaissance began nearly a century before Gutenberg invented his printing press when 14th-century political leaders in Italian city-states like Rome and Florence set out to revive the Ancient Roman educational system that had produced giants like Caesar, Cicero and Seneca.

One of the chief projects of the early Renaissance was to find long-lost works by figures like Plato and Aristotle and republish them. Wealthy patrons funded expensive expeditions across the Alps in search of isolated monasteries. Italian emissaries spent years in the Ottoman Empire learning enough Ancient Greek and Arabic to translate and copy rare texts into Latin.

The operation to retrieve classic texts was in action long before the printing press, but publishing the texts had been arduously slow and prohibitively expensive for anyone other than the richest of the rich. Palmer says that one hand-copied book in the 14th century cost as much as a house and libraries cost a small fortune. The largest European library in 1300 was the university library of Paris, which had 300 total manuscripts.

By the 1490s, when Venice was the book-printing capital of Europe, a printed copy of a great work by Cicero only cost a month’s salary for a school teacher. The printing press didn’t launch the Renaissance, but it vastly accelerated the rediscovery and sharing of knowledge.

“Suddenly, what had been a project to educate only the few wealthiest elite in this society could now become a project to put a library in every medium-sized town, and a library in the house of every reasonably wealthy merchant family,” says Palmer.

3. Martin Luther Becomes the First Best-Selling Author

Martin Luther nailing his 95 theses on the door of Wittenberg castle church.

Ipsumpix/Corbis/Getty Images

There’s a famous quote attributed to German religious reformer Martin Luther that sums up the role of the printing press in the Protestant Reformation: “Printing is the ultimate gift of God and the greatest one.”

Luther wasn’t the first theologian to question the Church, but he was the first to widely publish his message. Other “heretics” saw their movements quickly quashed by Church authorities and the few copies of their writings easily destroyed. But the timing of Luther’s crusade against the selling of indulgences coincided with an explosion of printing presses across Europe.

6 Reasons the Dark Ages Weren’t So Dark

As the legend goes, Luther nailed his “95 Theses” to the church door in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517. Palmer says that broadsheet copies of Luther’s document were being printed in London as quickly as 17 days later.

Thanks to the printing press and the timely power of his message, Luther became the world’s first best-selling author. Luther’s translation of the New Testament into German sold 5,000 copies in just two weeks. From 1518 to 1525, Luther’s writings accounted for a third of all books sold in Germany and his German Bible went through more than 430 editions.

4. Printing Powers the Scientific Revolution

Tables from Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus’ pioneering text “De revolutionibus orbium caelestium” (On the revolution of heavenly spheres), 1543, which represents his complete work.

SSPL/Getty Images

The English philosopher Francis Bacon, who’s credited with developing the scientific method, wrote in 1620 that the three inventions that forever changed the world were gunpowder, the nautical compass and the printing press.

For millennia, science was a largely solitary pursuit. Great mathematicians and natural philosophers were separated by geography, language and the sloth-like pace of hand-written publishing. Not only were handwritten copies of scientific data expensive and hard to come by, they were also prone to human error.

With the newfound ability to publish and share scientific findings and experimental data with a wide audience, science took great leaps forward in the 16th and 17th centuries. When developing his sun-centric model of the galaxy in the early 1500s, for example, Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus relied not only on his own heavenly observations, but on printed astronomical tables of planetary movements.

When historian Elizabeth Eisenstein wrote her 1980 book about the impact of the printing press, she said that its biggest gift to science wasn’t necessarily the speed at which ideas could spread with printed books, but the accuracy with which the original data were copied. With printed formulas and mathematical tables in hand, scientists could trust the fidelity of existing data and devote more energy to breaking new ground.

5. Fringe Voices Get a Platform

A printing press being used to make books during the 16th century.

Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images

“Whenever a new information technology comes along, and this includes the printing press, among the very first groups to be ‘loud’ in it are the people who were silenced in the earlier system, which means radical voices,” says Palmer.

It takes effort to adopt a new information technology, whether it’s the ham radio, an internet bulletin board, or Instagram. The people most willing to take risks and make the effort to be early adopters are those who had no voice before that technology existed.

“In the print revolution, that meant radical heresies, radical Christian splinter groups, radical egalitarian groups, critics of the government,” says Palmer. “The Protestant Reformation is only one of many symptoms of print enabling these voices to be heard.”

As critical and alternative opinions entered the public discourse, those in power tried to censor it. Before the printing press, censorship was easy. All it required was killing the “heretic” and burning his or her handful of notebooks.

But after the printing press, Palmer says it became nearly impossible to destroy all copies of a dangerous idea. And the more dangerous a book was claimed to be, the more the people wanted to read it. Every time the Church published a list of banned books, the booksellers knew exactly what they should print next.

6. From Public Opinion to Popular Revolution

Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” was printed in 1776.

VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images

During the Enlightenment era, philosophers like John Locke, Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau were widely read among an increasingly literate populace. Their elevation of critical reasoning above custom and tradition encouraged people to question religious authority and prize personal liberty.

Increasing democratization of knowledge in the Enlightenment era led to the development of public opinion and its power to topple the ruling elite. Writing in pre-Revolution France, Louis-Sebástien Mercier declared:

“A great and momentous revolution in our ideas has taken place within the last thirty years. Public opinion has now become a preponderant power in Europe, one that cannot be resisted… one may hope that enlightened ideas will bring about the greatest good on Earth and that tyrants of all kinds will tremble before the universal cry that echoes everywhere, awakening Europe from its slumbers.”

“[Printing] is the most beautiful gift from heaven,” continues Mercier. “It soon will change the countenance of the universe… Printing was only born a short while ago, and already everything is heading toward perfection… Tremble, therefore, tyrants of the world! Tremble before the virtuous writer!”

Even the illiterate couldn’t resist the attraction of revolutionary Enlightenment authors, Palmer says. When Thomas Paine published “Common Sense” in 1776, the literacy rate in the American colonies was around 15 percent, yet there were more copies printed and sold of the revolutionary tract than the entire population of the colonies.

7. Machines ‘Steal Jobs’ From Workers

Benjamin Franklin and associates at Franklin’s printing press in 1732.

GraphicaArtis/Getty Images

The Industrial Revolution didn’t get into full swing in Europe until the mid-18th century, but you can make the argument that the printing press introduced the world to the idea of machines “stealing jobs” from workers.

Before Gutenberg’s paradigm-shifting invention, scribes were in high demand. Bookmakers would employ dozens of trained artisans to painstakingly hand-copy and illuminate manuscripts. But by the late 15th century, the printing press had rendered their unique skillset all but obsolete.

On the flip side, the huge demand for printed material spawned the creation of an entirely new industry of printers, brick-and-mortar booksellers and enterprising street peddlers. Among those who got his start as a printer’s apprentice was future Founding Father, Benjamin Franklin.