Computer Science > Computers and Society

An Overview of Catastrophic AI Risks

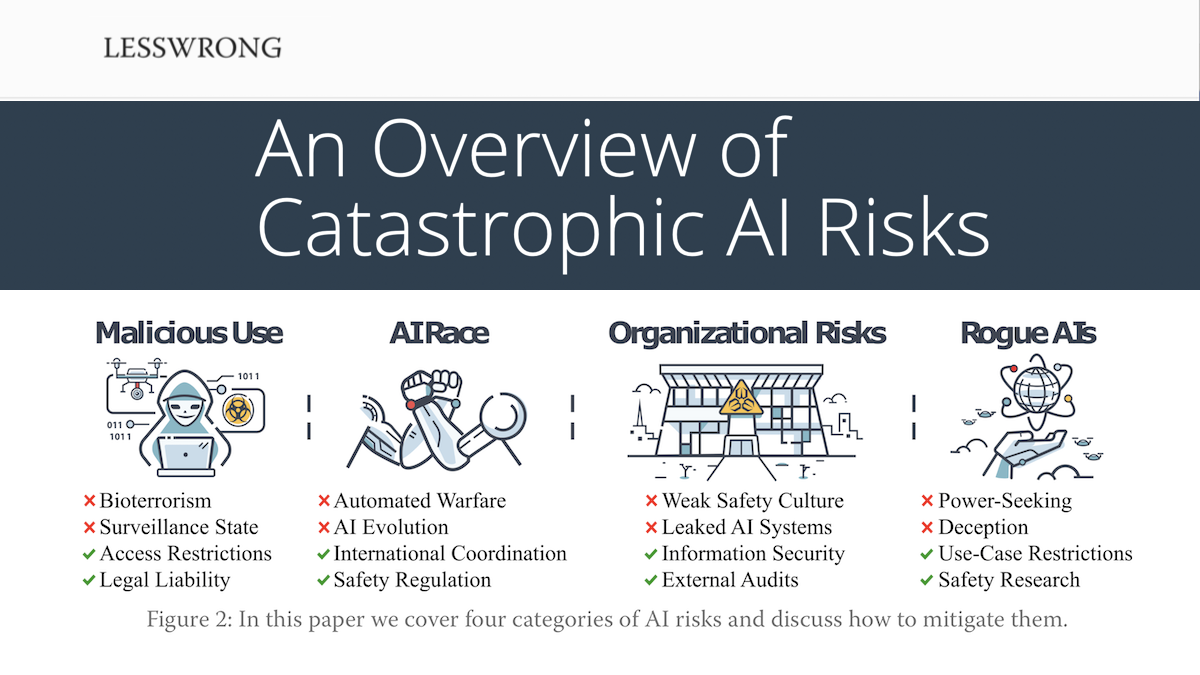

Rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have sparked growing concerns among experts, policymakers, and world leaders regarding the potential for increasingly advanced AI systems to pose catastrophic risks. Although numerous risks have been detailed separately, there is a pressing need for a systematic discussion and illustration of the potential dangers to better inform efforts to mitigate them. This paper provides an overview of the main sources of catastrophic AI risks, which we organize into four categories: malicious use, in which individuals or groups intentionally use AIs to cause harm; AI race, in which competitive environments compel actors to deploy unsafe AIs or cede control to AIs; organizational risks, highlighting how human factors and complex systems can increase the chances of catastrophic accidents; and rogue AIs, describing the inherent difficulty in controlling agents far more intelligent than humans. For each category of risk, we describe specific hazards, present illustrative stories, envision ideal scenarios, and propose practical suggestions for mitigating these dangers. Our goal is to foster a comprehensive understanding of these risks and inspire collective and proactive efforts to ensure that AIs are developed and deployed in a safe manner. Ultimately, we hope this will allow us to realize the benefits of this powerful technology while minimizing the potential for catastrophic outcomes.

Submission history

From: Dan Hendrycks [view email] [v1] Wed, 21 Jun 2023 03:35:06 UTC (5,234 KB)

[v2] Mon, 26 Jun 2023 17:26:07 UTC (5,235 KB)

Executive Summary

Artificial intelligence (AI) has seen rapid advancements in recent years, raising concerns among AI experts, policymakers, and world leaders about the potential risks posed by advanced AIs. As with all powerful technologies, AI must be handled with great responsibility to manage the risks and harness its potential for the betterment of society. However, there is limited accessible information on how catastrophic or existential AI risks might transpire or be addressed. While numerous sources on this subject exist, they tend to be spread across various papers, often targeted toward a narrow audience or focused on specific risks. In this paper, we provide an overview of the main sources of catastrophic AI risk, which we organize into four categories:

Malicious use. Actors could intentionally harness powerful AIs to cause widespread harm. Specific risks include bioterrorism enabled by AIs that can help humans create deadly pathogens; the deliberate dissemination of uncontrolled AI agents; and the use of AI capabilities for propaganda, censorship, and surveillance. To reduce these risks, we suggest improving biosecurity, restricting access to the most dangerous AI models, and holding AI developers legally liable for damages caused by their AI systems.

AI race. Competition could pressure nations and corporations to rush the development of AIs and cede control to AI systems. Militaries might face pressure to develop autonomous weapons and use AIs for cyberwarfare, enabling a new kind of automated warfare where accidents can spiral out of control before humans have the chance to intervene. Corporations will face similar incentives to automate human labor and prioritize profits over safety, potentially leading to mass unemployment and dependence on AI systems. We also discuss how evolutionary dynamics might shape AIs in the long run. Natural selection among AIs may lead to selfish traits, and the advantages AIs have over humans could eventually lead to the displacement of humanity. To reduce risks from an AI race, we suggest implementing safety regulations, international coordination, and public control of general-purpose AIs.

Organizational risks. Organizational accidents have caused disasters including Chernobyl, Three Mile Island, and the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster. Similarly, the organizations developing and deploying advanced AIs could suffer catastrophic accidents, particularly if they do not have a strong safety culture. AIs could be accidentally leaked to the public or stolen by malicious actors. Organizations could fail to invest in safety research, lack understanding of how to reliably improve AI safety faster than general AI capabilities, or suppress internal concerns about AI risks. To reduce these risks, better organizational cultures and structures can be established, including internal and external audits, multiple layers of defense against risks, and military-grade information security.

Rogue AIs. A common and serious concern is that we might lose control over AIs as they become more intelligent than we are. AIs could optimize flawed objectives to an extreme degree in a process called proxy gaming. AIs could experience goal drift as they adapt to a changing environment, similar to how people acquire and lose goals throughout their lives. In some cases, it might be instrumentally rational for AIs to become power-seeking. We also look at how and why AIs might engage in deception, appearing to be under control when they are not. These problems are more technical than the first three sources of risk. We outline some suggested research directions for advancing our understanding of how to ensure AIs are controllable.

Throughout each section, we provide illustrative scenarios that demonstrate more concretely how the sources of risk might lead to catastrophic outcomes or even pose existential threats. By offering a positive vision of a safer future in which risks are managed appropriately, we emphasize that the emerging risks of AI are serious but not insurmountable. By proactively addressing these risks, we can work toward realizing the benefits of AI while minimizing the potential for catastrophic outcomes.

Appendix: Frequently Asked Questions

Since AI catastrophic risk is a new challenge, albeit one that has been the subject of extensive speculation in popular culture, there are many questions about if and how it might manifest. Although public attention may focus on the most dramatic risks, some of the more mundane sources of risk discussed in this document may be equally severe. In addition, many of the simplest ideas one might have for addressing these risks turn out to be insufficient on closer inspection. We will now address some of the most common questions and misconceptions about catastrophic AI risk.

1. Shouldn’t we address AI risks in the future when AIs can actually do everything a human can?

It is not necessarily the case that human-level AI is far in the future. Many top AI researchers think that human-level AI will be developed fairly soon, so urgency is warranted. Furthermore, waiting until the last second to start addressing AI risks is waiting until it’s too late. Just as waiting to fully understand COVID-19 before taking any action would have been a mistake, it is ill-advised to procrastinate on safety and wait for malicious AIs or bad actors to cause harm before taking AI risks seriously.

One might argue that since AIs cannot even drive cars or fold clothes yet, there is no need to worry. However, AIs do not need all human capabilities to pose serious threats; they only need a few specific capabilities to cause catastrophe. For example, AIs with the ability to hack computer systems or create bioweapons would pose significant risks to humanity, even if they couldn’t iron a shirt. Furthermore, the development of AI capabilities has not followed an intuitive pattern where tasks that are easy for humans are the first to be mastered by AIs. Current AIs can already perform complex tasks such as writing code and designing novel drugs, even while they struggle with simple physical tasks. Like climate change and COVID-19, AI risk should be addressed proactively, focusing on prevention and preparedness rather than waiting for consequences to manifest themselves, as they may already be irreparable by that point.

2. Since humans program AIs, shouldn’t we be able to shut them down if they become dangerous?

While humans are the creators of AI, maintaining control over these creations as they evolve and become more autonomous is not a guaranteed prospect. The notion that we could simply “shut them down” if they pose a threat is more complicated than it first appears.

First, consider the rapid pace at which an AI catastrophe could unfold. Analogous to preventing a rocket explosion after detecting a gas leak, or halting the spread of a virus already rampant in the population, the time between recognizing the danger and being able to prevent or mitigate it could be precariously short.

Second, over time, evolutionary forces and selection pressures could create AIs exhibiting selfish behaviors that make them more fit, such that it is harder to stop them from propagating their information. As these AIs continue to evolve and become more useful, they may become central to our societal infrastructure and daily lives, analogous to how the internet has become an essential, non-negotiable part of our lives with no simple off-switch. They might manage critical tasks like running our energy grids, or possess vast amounts of tacit knowledge, making them difficult to replace. As we become more reliant on these AIs, we may voluntarily cede control and delegate more and more tasks to them. Eventually, we may find ourselves in a position where we lack the necessary skills or knowledge to perform these tasks ourselves. This increasing dependence could make the idea of simply “shutting them down” not just disruptive, but potentially impossible.

Similarly, some people would strongly resist or counteract attempts to shut them down, much like how we cannot permanently shut down all illegal websites or shut down Bitcoin—many people are invested in their continuation. As AIs become more vital to our lives and economies, they could develop a dedicated user base, or even a fanbase, that could actively resist attempts to restrict or shut down AIs. Likewise, consider the complications arising from malicious actors. If malicious actors have control over AIs, they could potentially use them to inflict harm. Unlike AIs under benign control, we wouldn’t have an off-switch for these systems.

Next, as some AIs become more and more human-like, some may argue that these AIs should have rights. They could argue that not giving them rights is a form of slavery and is morally abhorrent. Some countries or jurisdictions may grant certain AIs rights. In fact, there is already momentum to give AIs rights. Sophia the Robot has already been granted citizenship in Saudi Arabia, and Japan granted a robot named Paro a koseki, or household registry, “which confirms the robot’s Japanese citizenship” [135]. There may come a time when switching off an AI could be likened to murder. This would add a layer of political complexity to the notion of a simple “off-switch.”

Lastly, as AIs gain more power and autonomy, they might develop a drive for “self-preservation.” This would make them resistant to shutdown attempts and could allow them to anticipate and circumvent our attempts at control. Given these challenges, it’s critical that we address potential AI risks proactively and put robust safeguards in place well before these problems arise.

3. Why can’t we just tell AIs to follow Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics?

Asimov’s laws, often highlighted in AI discussions, are insightful but inherently flawed. Indeed, Asimov himself acknowledges their limitations in his books and uses them primarily as an illustrative tool. Take the first law, for example. This law dictates that robots “may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm,” but the definition of “harm” is very nuanced. Should your home robot prevent you from leaving your house and entering traffic because it could potentially be harmful? On the other hand, if it confines you to the home, harm might befall you there as well. What about medical decisions? A given medication could have harmful side effects for some people, but not administering it could be harmful as well. Thus, there would be no way to follow this law. More importantly, the safety of AI systems cannot be ensured merely through a list of axioms or rules. Moreover, this approach would fail to address numerous technical and sociotechnical problems, including goal drift, proxy gaming, and competitive pressures. Therefore, AI safety requires a more comprehensive, proactive, and nuanced approach than simply devising a list of rules for AIs to adhere to.

4. If AIs become more intelligent than people, wouldn’t they be wiser and more moral? That would mean they would not aim to harm us.

The idea of AIs becoming inherently more moral as they increase in intelligence is an intriguing concept, but rests on uncertain assumptions that can’t guarantee our safety. Firstly, it assumes that moral claims can be true or false and their correctness can be discovered through reason. Secondly, it assumes that the moral claims that are really true would be beneficial for humans if AIs apply them. Thirdly, it assumes that AIs that know about morality will choose to make their decisions based on morality and not based on other considerations. An insightful parallel can be drawn to human sociopaths, who, despite their intelligence and moral awareness, do not necessarily exhibit moral inclinations or actions. This comparison illustrates that knowledge of morality does not always lead to moral behavior. Thus, while some of the above assumptions may be true, betting the future of humanity on the claim that all of them are true would be unwise.

Assuming AIs could indeed deduce a moral code, its compatibility with human safety and wellbeing is not guaranteed. For example, AIs whose moral code is to maximize wellbeing for all life might seem good for humans at first. However, they might eventually decide that humans are costly and could be replaced with AIs that experience positive wellbeing more efficiently. AIs whose moral code is not to kill anyone would not necessarily prioritize human wellbeing or happiness, so our lives may not necessarily improve if the world begins to be increasingly shaped by and for AIs. Even AIs whose moral code is to improve the wellbeing of the worst-off in society might eventually exclude humans from the social contract, similar to how many humans view livestock. Finally, even if AIs discover a moral code that is favorable to humans, they may not act on it due to potential conflicts between moral and selfish motivations. Therefore, the moral progression of AIs is not inherently tied to human safety or prosperity.

5. Wouldn’t aligning AI systems with current values perpetuate existing moral failures?

There are plenty of moral failures in society today that we would not want powerful AI systems to perpetuate into the future. If the ancient Greeks had built powerful AI systems, they might have imbued them with many values that people today would find unethical. However, this concern should not prevent us from developing methods to control AI systems.

To achieve any value in the future, life needs to exist in the first place. Losing control over advanced AIs could constitute an existential catastrophe. Thus, uncertainty over what ethics to embed in AIs is not in tension with whether to make AIs safe.

To accommodate moral uncertainty, we should deliberately build AI systems that are adaptive and responsive to evolving moral views. As we identify moral mistakes and improve our ethical understanding, the goals we give to AIs should change accordingly—though allowing AI goals to drift unintentionally would be a serious mistake. AIs could also help us better live by our values. For individuals, AIs could help people have more informed preferences by providing them with ideal advice [132].

Separately, in designing AI systems, we should recognize the fact of reasonable pluralism, which acknowledges that reasonable people can have genuine disagreements about moral issues due to their different experiences and beliefs [136]. Thus, AI systems should be built to respect a diverse plurality of human values, perhaps by using democratic processes and theories of moral uncertainty. Just as people today convene to deliberate on disagreements and make consensus decisions, AIs could emulate a parliament representing different stakeholders, drawing on different moral views to make real-time decisions [55, 137]. It is crucial that we deliberately design AI systems to account for safety, adaptivity, stakeholders with different values.

6. Wouldn’t the potential benefits that AIs could bring justify the risks?

The potential benefits of AI could justify the risks if the risks were negligible. However, the chance of existential risk from AI is too high for it to be prudent to rapidly develop AI. Since extinction is forever, a far more cautious approach is required. This is not like weighing the risks of a new drug against its potential side effects, as the risks are not localized but global. Rather, a more prudent approach is to develop AI slowly and carefully such that existential risks are reduced to a negligible level (e.g., under 0.001% per century).

Some influential technology leaders are accelerationists and argue for rapid AI development to barrel ahead toward a technological utopia. This techno-utopian viewpoint sees AI as the next step down a predestined path toward unlocking humanity’s cosmic endowment. However, the logic of this viewpoint collapses on itself when engaged on its own terms. If one is concerned with the cosmic stakes of developing AI, we can see that even then it’s prudent to bring existential risk to a negligible level. The techno-utopians suggest that delaying AI costs humanity access to a new galaxy each year, but if we go extinct, we could lose the cosmos. Thus, the prudent path is to delay and safely prolong AI development, prioritizing risk reduction over acceleration, despite the allure of potential benefits.

7. Wouldn’t increasing attention on catastrophic risks from AIs drown out today’s urgent risks from AIs?

Focusing on catastrophic risks from AIs doesn’t mean ignoring today’s urgent risks; both can be addressed simultaneously, just as we can concurrently conduct research on various different diseases or prioritize mitigating risks from climate change and nuclear warfare at once. Additionally, current risks from AI are also intrinsically related to potential future catastrophic risks, so tackling both is beneficial. For example, extreme inequality can be exacerbated by AI technologies that disproportionately benefit the wealthy, while mass surveillance using AI could eventually facilitate unshakeable totalitarianism and lock-in. This demonstrates the interconnected nature of immediate concerns and long-term risks, emphasizing the importance of addressing both categories thoughtfully.

Additionally, it’s crucial to address potential risks early in system development. As illustrated by Frola and Miller in their report for the Department of Defense, approximately 75 percent of the most critical decisions impacting a system’s safety occur early in its development [138]. Ignoring safety considerations in the early stages often results in unsafe design choices that are highly integrated into the system, leading to higher costs or infeasibility of retrofitting safety solutions later. Hence, it is advantageous to start addressing potential risks early, regardless of their perceived urgency.

8. Aren’t many AI researchers working on making AIs safe?

Few researchers are working to make AI safer. Currently, approximately 2 percent of papers published at top machine learning venues are safety-relevant [105]. Most of the other 98 percent focus on building more powerful AI systems more quickly. This disparity underscores the need for more balanced efforts. However, the proportion of researchers alone doesn’t equate to overall safety. AI safety is a sociotechnical problem, not just a technical problem. Thus, it requires more than just technical research. Comfort should stem from rendering catastrophic AI risks negligible, not merely from the proportion of researchers working on making AIs safe.

9. Since it takes thousands of years to produce meaningful changes, why do we have to worry about evolution being a driving force in AI development?

Although the biological evolution of humans is slow, the evolution of other organisms, such as fruit flies or bacteria, can be extremely quick, demonstrating the diverse time scales at which evolution operates. The same rapid evolutionary changes can be observed in non-biological structures like software, which evolve much faster than biological entities. Likewise, one could expect AIs to evolve very quickly as well. The rate of AI evolution may be propelled by intense competition, high variation due to diverse forms of AIs and goals given to them, and the ability of AIs to rapidly adapt. Consequently, intense evolutionary pressures may be a driving force in the development of AIs.

10. Wouldn’t AIs need to have a power-seeking drive to pose a serious risk?

While power-seeking AI poses a risk, it is not the only scenario that could potentially lead to catastrophe. Malicious or reckless use of AIs can be equally damaging without the AI itself seeking power. Additionally, AIs might engage in harmful actions through proxy gaming or goal drift without intentionally seeking power. Furthermore, society’s trend toward automation, driven by competitive pressures, is gradually increasing the influence of AIs over humans. Hence, the risk does not solely stem from AIs seizing power, but also from humans ceding power to AIs.

11. Isn’t the combination of human intelligence and AI superior to AI alone, so that there is no need to worry about unemployment or humans becoming irrelevant?

While it’s true that human-computer teams have outperformed computers alone in the past, these have been temporary phenomena. For example, “cyborg chess” is a form of chess where humans and computers work together, which was historically superior to humans or computers alone. However, advancements in computer chess algorithms have eroded the advantage of human-computer teams to such an extent that there is arguably no longer any advantage compared to computers alone. To take a simpler example, no one would pit a human against a simple calculator for long division. A similar progression may occur with AIs. There may be an interim phase where humans and AIs can work together effectively, but the trend suggests that AIs alone could eventually outperform humans in various tasks while no longer benefiting from human assistance.

12. The development of AI seems unstoppable. Wouldn’t slowing it down dramatically or stopping it require something like an invasive global surveillance regime?

AI development primarily relies on high-end chips called GPUs, which can be feasibly monitored and tracked, much like uranium. Additionally, the computational and financial investments required to develop frontier AIs are growing exponentially, resulting in a small number of actors who are capable of acquiring enough GPUs to develop them. Therefore, managing AI growth doesn’t necessarily require invasive global surveillance, but rather a systematic tracking of high-end GPU usage.