Imagine what a Super Artificial Intelligent (SAI) could do to our digital infrastructure…

“I would guess that SAI can hack its way into anything without relying on backdoors.” — Roman V. Yampolskiy, Ph.D.

A GOOD READ: AI: Unexplainable, Unpredictable, Uncontrollable — Roman V. Yampolskiy, Ph.D.

THE GUARDIAN. TechScape: How one man stopped a potentially massive cyber-attack – by accident

An unknown attacker carefully infiltrated Linux over Easter, and very nearly gained access to millions of computers – were it not for one mildly inconvenienced developer

By Alex Hern

Tue 2 Apr 2024

How was your Easter bank holiday? Did you use it well by, for instance, preventing a globally destructive cyber-attack? No? Try harder, then.

This weekend, a cautious, longstanding and very nearly successful attempt to insert a backdoor into a widely used piece of open-source software was thwarted – effectively by accident. From Dan Goodin at Ars Technica:

Researchers have found a malicious backdoor in a compression tool that made its way into widely used Linux distributions, including those from Red Hat and Debian.

Because the backdoor was discovered before the malicious versions of xz Utils were added to production versions of Linux, “it’s not really affecting anyone in the real world”, Will Dormann, a senior vulnerability analyst at security firm Analygence, said in an online interview. “BUT that’s only because it was discovered early due to bad actor sloppiness. Had it not been discovered, it would have been catastrophic to the world.”

The attempted hack is what is known as a “supply chain” attack. By carefully and slowly pushing updates to a little-known compression tool shipped with some Linux distributions, a free and open-source operating system, the attacker very nearly ended up with a backdoor to millions of computers at once. Whether the intention was to bide their time and then use that access for a mass hacking campaign or to execute a very patient and targeted attack on a single user is unclear at this time, though the patient and methodical nature of the attack is enough to have observers speculating that a state actor was behind it.

The backdoor itself was added to the tool by one of its two main developers, who had spent three years making real and useful contributions and the past two being one of the two official maintainers. There is still the chance the account was compromised, but if it was, it was an extremely cautious takeover: the malicious code was added to the software periodically over a long period of time, with plausible explanations given every time, and when the final backdoored version was complete, the same user headed over to the developer site for one popular version of Linux to ask that it use the updated version as soon as possible since it supposedly fixed critical bugs.

And it came so close to being public. The backdoored version was shipped in the beta versions of three different versions of Linux, and for two days, in the main release of one distribution, Kali Linux. When there, it allowed someone with the right private key to start a new encrypted connection and hijack the machine entirely.

So how was it spotted? A single Microsoft developer was annoyed that a system was running slowly. That’s it. The developer, Andres Freund, was trying to uncover why a system running a beta version of Debian, a Linux distribution, was lagging when making encrypted connections. That lag was all of half a second, for logins. That’s it: before, it took Freund 0.3s to login, and after, it took 0.8s. That annoyance was enough to cause him to break out the metaphorical spanner and pull his system apart to find the cause of the problem.

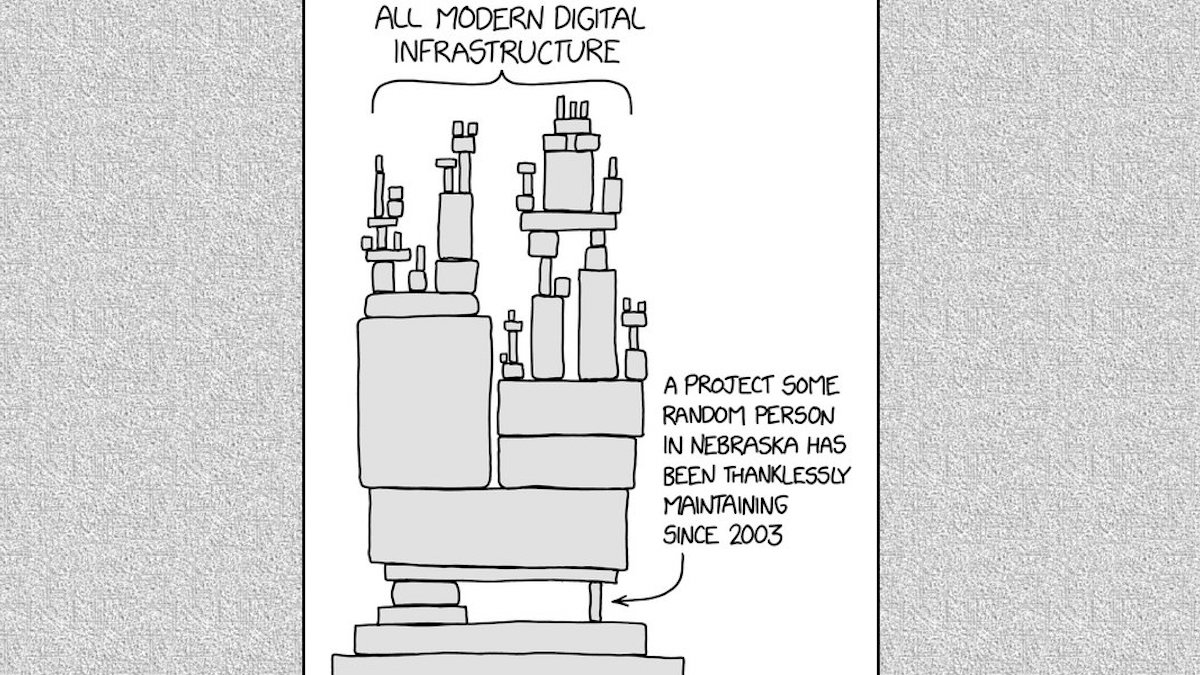

Many hands make light work, and many eyes make shallow bugs. That’s the idea, at least, and sometimes it works. We discussed last month the ways in which the open source world can fail to live up to expectations:

Giving software away for free is great for a whole host of reasons – but quite bad at funding continued development of that software. There have been loads of attempts to fix that, from models of development where the software is free but the support is paid, to big companies directly hiring maintainers of important open-source projects. Lots of projects have ended up in a tip or supporter-focused model (remind you of anyone?), which can work for big complex tasks but falls down for some of the simplest – yet most widely used – pieces of work.

The attack on xz Utils nearly became another example of the risks of relying on volunteer work to underpin some of the most important digital infrastructure in the world. A harried maintainer with little time to spare on a side project was suddenly offered help, and came under pressure to accept it – likely from exactly the same group, posting under a few fake names. Slowly cuckooed out of his own project, things nearly turned very nasty indeed.

But this case also shows the benefits of the approach. Supply chain attacks aren’t unique to the open source world, and the vague structure of the attack – getting a job building an underexamined component of critical infrastructure, and slowly and carefully working to introduce a secret weakness into it – is something that can, and does, happen in normal businesses too.

What doesn’t happen is being able to tear apart the problematic software piece by piece, and track down exactly the moment when a malicious backdoor was introduced. If a supply chain attack succeeds against a closed business like Apple or Google, even discovering it is there at all is wildly difficult for third-parties, and fixing it is effectively impossible.

Learn more:

- Did One Guy Just Stop a Huge Cyberattack? A Microsoft engineer noticed something was off on a piece of software he worked on. He soon discovered someone was probably trying to gain access to computers all over the world. – The New York Times