Learn more about symbiosis.

Nature. The Symbiotic Sea Slug Elysia chlorotica

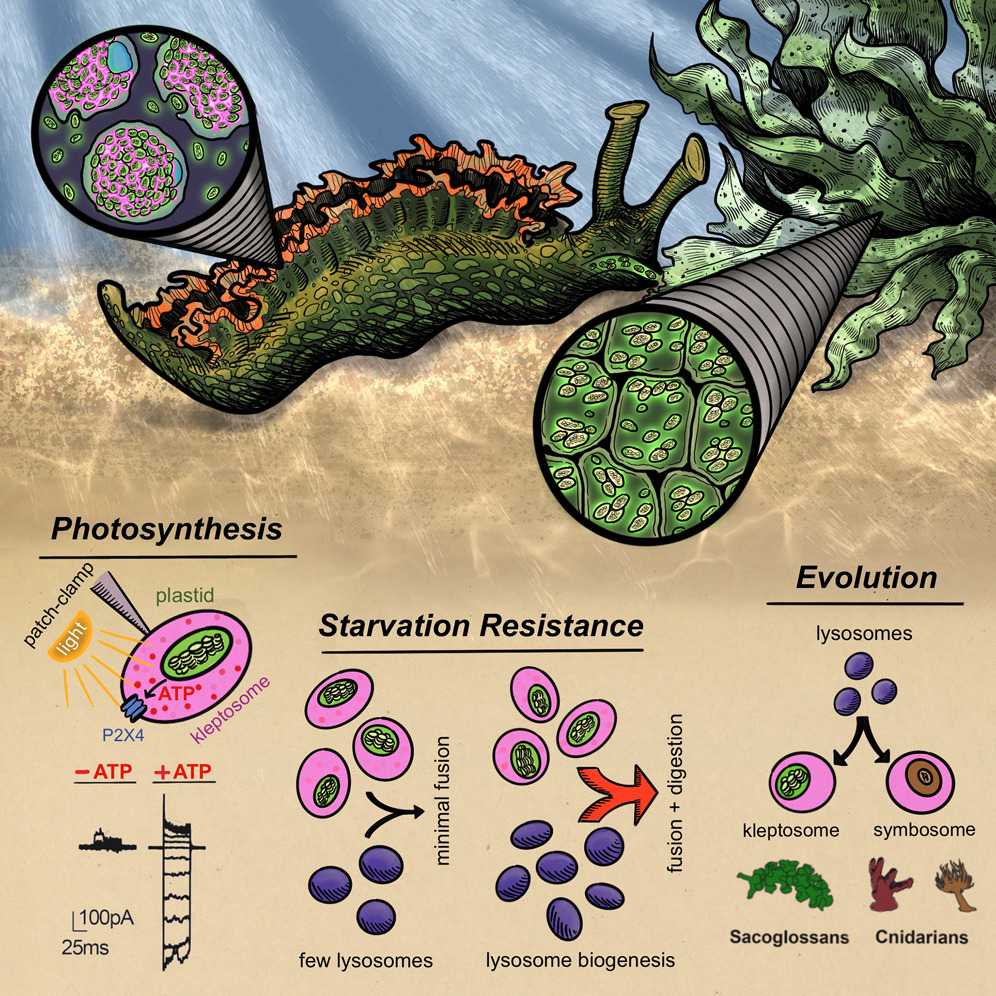

A host organelle integrates stolen chloroplasts for animal photosynthesis

Abstract. Eukaryotic life evolved over a billion years ago when ancient cells engulfed and integrated prokaryotes to become modern mitochondria and chloroplasts. Sacoglossan “solar-powered” sea slugs possess the ability to acquire organelles within a single lifetime by selectively retaining consumed chloroplasts that remain photosynthetically active for nearly a year. The mechanism for this “animal photosynthesis” remains unknown. Here, we discovered that foreign chloroplasts are housed within novel, host-derived organelles we term “kleptosomes.” Kleptosomes use ATP-sensitive ion channels to maintain a luminal environment that supports chloroplast photosynthesis and longevity. Upon slug starvation, kleptosomes digest stored chloroplasts for additional nutrients, thereby serving as a food source. We leveraged this discovery to find that organellar retention and digestion of photosynthetic cargo has convergently evolved in other photosynthetic animals, including corals and anemones. Thus, our study reveals mechanisms underlying the long-term acquisition and evolutionary incorporation of intracellular symbionts into organelles that support complex cellular function.

A draft genome assembly of the solar-powered sea slug Elysia chlorotica

Abstract Elysia chlorotica, a sacoglossan sea slug found off the East Coast of the United States, is well-known for its ability to sequester chloroplasts from its algal prey and survive by photosynthesis for up to 12 months in the absence of food supply. Here we present a draft genome assembly of E. chlorotica that was generated using a hybrid assembly strategy with Illumina short reads and PacBio long reads. The genome assembly comprised 9,989 scaffolds, with a total length of 557 Mb and a scaffold N50 of 442 kb. BUSCO assessment indicated that 93.3% of the expected metazoan genes were completely present in the genome assembly. Annotation of the E. chlorotica genome assembly identified 176 Mb (32.6%) of repetitive sequences and a total of 24,980 protein-coding genes. We anticipate that the annotated draft genome assembly of the E. chlorotica sea slug will promote the investigation of sacoglossan genetics, evolution, and particularly, the genetic signatures accounting for the long-term functioning of algal chloroplasts in an animal.

Active Host Response to Algal Symbionts in the Sea Slug Elysia chlorotica

Abstract. Sacoglossan sea slugs offer fascinating systems to study the onset and persistence of algal-plastid symbioses. Elysia chlorotica is particularly noteworthy because it can survive for months, relying solely on energy produced by ingested plastids of the stramenopile alga Vaucheria litorea that are sequestered in cells lining its digestive diverticula. How this animal can maintain the actively photosynthesizing organelles without replenishment of proteins from the lost algal nucleus remains unknown. Here, we used RNA-Seq analysis to test the idea that plastid sequestration leaves a significant signature on host gene expression during E. chlorotica development. Our results support this hypothesis and show that upon exposure to and ingestion of V. litorea plastids, genes involved in microbe-associated molecular patterns and oxidative stress-response mechanisms are significantly up-regulated. Interestingly, our results with E. chlorotica mirror those found with corals that maintain dinoflagellates as intact cells in symbiosomes, suggesting parallels between these animal–algal symbiotic interactions.

The Sea Slug Defying Biological Orthodoxy

Symbiosis may be more important to evolution than scientists once thought.

By Zoë Schlanger