In The Assistance Game the human and assistant share a reward function, but it depends on reward parameters that are initially known only to the human (provided however there is the problem that the human does not necessarily know how to define the preference at the start, and hence the solution wherein the assistant must discover the human preference).

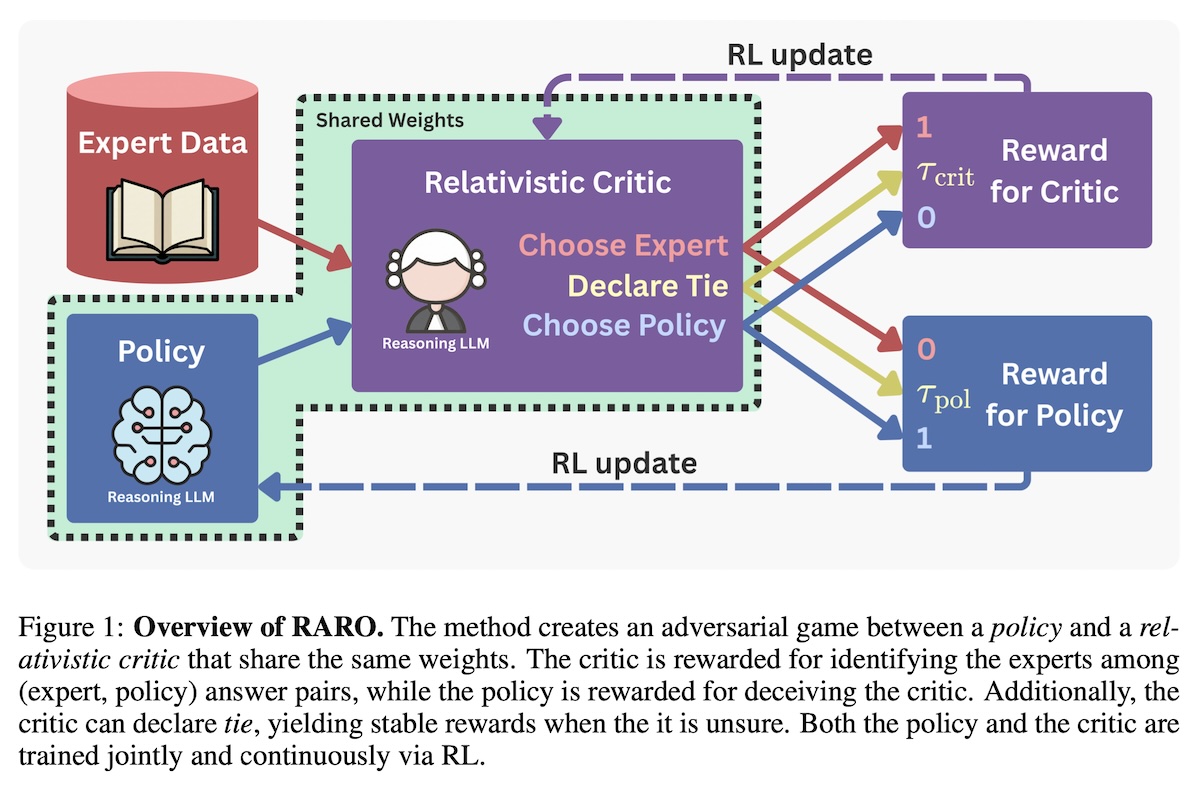

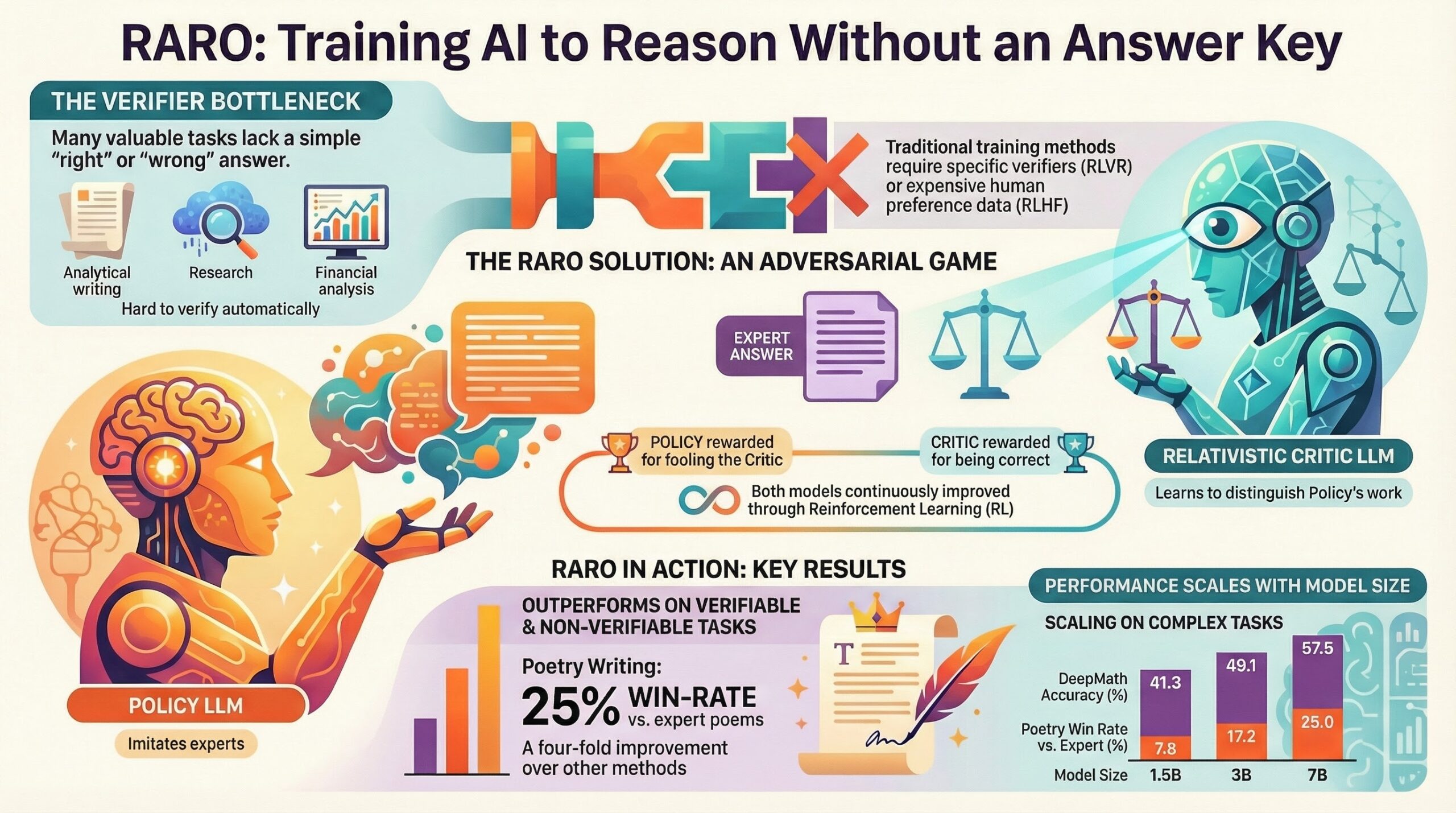

In Relativistic Adversarial Reasoning Optimization (RARO) the reward is discovered in the game that learns strong reasoning capabilities from only expert demonstrations via Inverse Reinforcement Learning. The RARO method sets up an adversarial game between a policy and a relativistic critic: the policy learns to mimic expert answers, while the critic aims to identify the experts among (expert, policy) answer pairs. Both the policy and the critic are trained jointly and continuously via RL, and RARO identifies the key stabilization techniques required for robust learning.

FOR EDUCATIONAL AND KNOWLEDGE SHARING PURPOSES ONLY. NOT-FOR-PROFIT. SEE COPYRIGHT DISCLAIMER.

AssistanceZero: Scalably Solving Assistance Games

Cassidy Laidlaw, Eli Bronstein, Timothy Guo, Dylan Feng, Lukas Berglund, Justin Svegliato, Stuart Russell, and Anca Dragan

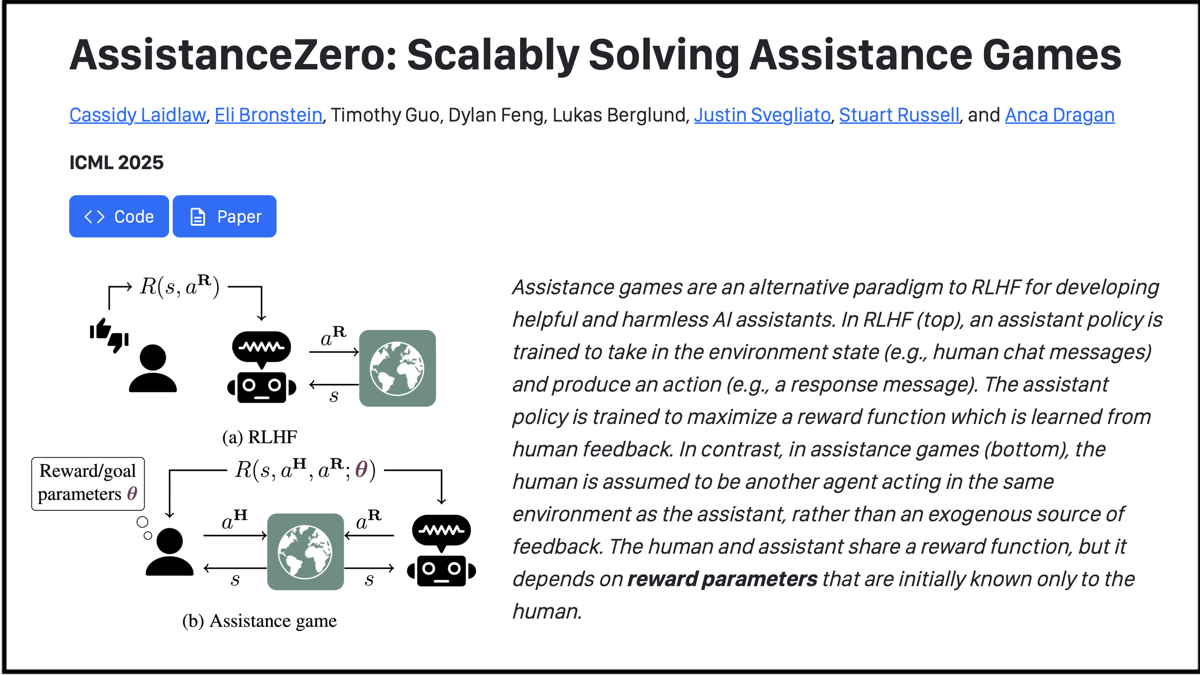

Assistance games are an alternative paradigm to RLHF for developing helpful and harmless AI assistants. In RLHF (top), an assistant policy is trained to take in the environment state (e.g., human chat messages) and produce an action (e.g., a response message). The assistant policy is trained to maximize a reward function which is learned from human feedback. In contrast, in assistance games (bottom), the human is assumed to be another agent acting in the same environment as the assistant, rather than an exogenous source of feedback. The human and assistant share a reward function, but it depends on reward parameters that are initially known only to the human.

Paper

We develop a scalable approach to solving assistance games, which are an alternative paradigm to RLHF for training helpful and harmless assistants. We demonstrate our approach in a new environment, the Minecraft Building Assistance Game (MBAG), where an assistant helps a user build a house that is unknown to the assistant. Here, we provide code for MBAG and the experiments in the paper. We also present videos from our human study.

Code

The code for MBAG and the experiments in the paper is available at https://github.com/cassidylaidlaw/minecraft-building-assistance-game. The README at that link contains instructions for running our assistants in MBAG.

Videos

Emergent behaviors from AssistanceZero

Our assistant trained for MBAG using assistance games learns to exhibit a variety of behaviors that are helpful to users. Here, we show three examples of emergent behaviors from AssistanceZero, our algorithm for solving assistance games. These are the same three examples shown in Figure 1 of the paper.

Learn more

PROMPT

THOUGHTS (30.8s)

Investigating AI Safety Papers

I’ve initiated a search for “The Assistance Game AI safety Stuart Russell” to pinpoint the seminal paper and related works. My focus has broadened to include “Cooperative Inverse Reinforcement Learning” (CIRL). The goal is to fully understand the foundational principles of this approach.

Compiling References for Assistance Game

I’m now expanding my search to include papers citing or building upon the Assistance Game framework to get a wider scientific perspective. I’m also looking into critiques, related terms like CIRL, and practical applications or experiments for the Assistance Game. My aim is to synthesize a comprehensive research report with a solid list of scientific references.

Identifying Key Research

I’ve homed in on “Cooperative Inverse Reinforcement Learning” (CIRL) as the cornerstone paper for “The Assistance Game,” along with Stuart Russell’s “Human Compatible.” These have been incredibly helpful in conceptualizing the problem.

Exploring Game Mechanics Further

I’m now diving deeper into the technical aspects. The search results gave me a good grasp of Assistance Games, their core purpose (value alignment), and how they relate to Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) and POMDPs. I’ve also found related papers: “The Off-Switch Game”, “Inverse Reward Design”, “AssistanceZero”, and an update on cooperative IRL.

Deepening the Research Dive

My recent efforts have focused on bolstering the theoretical underpinning and expanding the literature review. I’m actively pursuing more recent applications and experimental results to broaden my understanding beyond the initial examples. I am specifically targeting papers citing “Cooperative Inverse Reinforcement Learning” and related works to uncover the latest advancements. I’m also looking for detailed mathematical breakdowns to ensure I’ve grasped the technical components accurately.

Reviewing CIRL Details

I’ve been deeply immersed in the nuances of Cooperative Inverse Reinforcement Learning, or as some call it, the Assistance Game. I’ve compiled a detailed dossier on its core definition and underlying assumptions. Specifically, I’m focusing on the reward functions and how they relate to the game dynamics, which I am actively unpacking for deeper understanding.

Deconstructing the Framework

I’m now fully immersed in the mathematical underpinnings of this game, specifically the formal tuple definition. I’m unpacking the implications of the Coordinator-POMDP formulation, and how it differs from traditional IRL, especially regarding the human’s role as a cooperative teacher. I’m also examining the crucial principles, particularly the machine’s initial uncertainty about human preferences and the significance of human behavior as the primary source of information. I am also exploring extensions to the basic framework, such as the Off-Switch Game and Inverse Reward Design.

Evaluating Further Extensions

I’m now grappling with recent extensions to this game-theoretic IRL approach. I’m actively assessing “AssistanceZero,” as well as multi-principal assistance models. Considering real-world implications, I’m finding limitations, specifically the assumption of human rationality and the computational expense. Concerns about inner alignment, potential manipulation, and privacy are also coming to mind. It seems RLHF shares some similarities, especially sycophancy.

Seeking Concrete Applications

I’m now focusing on solidifying my understanding of the practical impact of Assistance Game research. While I possess a rich foundation, the pursuit of real-world deployments beyond the core AssistanceZero paper remains a priority. I’m actively seeking specific algorithms or tangible implementations that have emerged since 2023. Organizing references chronologically and thematically is the next step to facilitate the report’s structure.

Defining Report Structure

I’ve completed the initial content review. Now, I’m crystallizing the report’s organization. I’ll include an executive summary and delve into the conceptual foundation, formally covering the framework and theoretical results. Then, I’ll compare it to state-of-the-art methods, explore extensions and limitations, and offer critiques. I’ve curated a strong reference list, and the “Off-Switch Game” specific details are now clear.

Formulating Off-Switch Details

I’m now fully prepared to write about the “Off-Switch Game” aspects, building on my existing insights. I’ll include a formal definition, perhaps derived from a concise summary. I’m leveraging readily available snippets to construct a more profound analysis. I can now move forward with confidence.

RESULT (49.5s)

Executive Summary

The Assistance Game addresses the value alignment problem by modeling the human-AI relationship as a cooperative, partial-information game. In this game, the human knows the true reward function (preferences), but the AI does not. The AI’s optimal strategy is not to blindly maximize a hard-coded goal, but to infer the true goal from human behavior while acting to assist. This framework mathematically guarantees desirable safety behaviors, such as corrigibility (willingness to be corrected) and deference (allowing itself to be switched off), derived solely from the AI’s uncertainty about the true objective.

1. Conceptual Foundation: The Three Principles

Stuart Russell articulates the philosophy behind Assistance Games through three principles intended to replace the standard definition of AI:

- Altruism: The machine’s only objective is to maximize the realization of human preferences (values).

- Humility (Uncertainty): The machine is initially uncertain about what those preferences are.

- Observation: The ultimate source of information about human preferences is human behavior.

Key Insight: Uncertainty is a feature, not a bug. An AI that is certain of its objective will resist being switched off (since being off prevents it from achieving the goal). An AI that is uncertain will allow itself to be switched off, reasoning that the human knows better and that switching it off prevents it from doing something wrong (negative reward).

2. Mathematical Formulation: Cooperative Inverse Reinforcement Learning (CIRL)

The formal definition of an Assistance Game was provided in the seminal paper Cooperative Inverse Reinforcement Learning (NeurIPS 2016).

Definition

A CIRL game is defined as a two-player tuple: $$M = \langle S, {A_H, A_R}, T, {\Theta, R}, P_0, \gamma \rangle$$

- $S$: Set of world states.

- $A_H, A_R$: Sets of actions for the Human ($H$) and Robot ($R$).

- $T(s’ | s, a_H, a_R)$: Transition function (dynamics of the environment).

- $\Theta$: The set of possible reward parameters (the “true” objective).

- $R(s, \theta)$: The reward function, parametrized by $\theta$. Crucially, $H$ knows $\theta$, but $R$ does not.

- $P_0$: Initial probability distribution over states and $\theta$ (the robot’s prior).

- $\gamma$: Discount factor.

Mechanism

- Cooperative Game: Unlike standard Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) where the human acts alone and the robot watches, CIRL is a game where both act to maximize the same reward $R(s, \theta)$.

- Reduction to POMDP: The problem can be reduced to a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) from the robot’s perspective. The “state” for the robot is the physical world state plus the unknown human goal $\theta$.

- Active Teaching & Learning: The optimal policy pair $(\pi_H, \pi_R)$ involves the human acting pedagogically (performing actions that best reveal $\theta$ to the robot) and the robot acting to interpret these signals while managing the explore-exploit tradeoff (acting to gain information vs. acting to gain reward).

3. Key Theoretical Results & Extensions

A. The Off-Switch Game

- Paper: The Off-Switch Game (Hadfield-Menell et al., 2017)

- Concept: A simplified Assistance Game where the robot can act ($a$), wait ($w$), or switch itself off ($s$).

- Result: It is mathematically proven that if the robot is sufficiently uncertain about the reward of action $a$, it will choose to wait or allow the human to switch it off. As the robot’s certainty approaches 1 (dogmatism), the incentive to allow the off-switch vanishes. This formalizes why uncertainty is necessary for control.

B. Inverse Reward Design (IRD)

- Paper: Inverse Reward Design (Hadfield-Menell et al., 2017)

- Concept: Addresses the problem where a human specifies a proxy reward $\tilde{R}$ (e.g., “maximize points”) that correlates with the true reward $R$ in the training environment but fails in new contexts (e.g., “lava” was never seen in training).

- Mechanism: The AI treats $\tilde{R}$ not as the ground truth, but as evidence about the true reward $R$. This leads to risk-averse behavior in novel environments.

C. Multi-Principal Assistance Games

- Paper: Multi-Principal Assistance Games (Fickinger et al., 2020)

- Challenge: AI serving multiple humans with conflicting preferences.

- Result: This extends the framework to social choice theory. It highlights that an AI cannot simply “maximize the sum” without understanding trade-offs and distribution, requiring “collegial” mechanisms to infer aggregate preferences.

D. Scaling to Complex Environments (AssistanceZero)

- Paper: AssistanceZero: Scalably Solving Assistance Games (2024/2025 timeframe)

- Innovation: Uses Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) similar to AlphaZero to solve the intractable POMDPs inherent in Assistance Games. It explicitly models the human’s latent goals and plans under uncertainty, demonstrating success in complex domains like Minecraft.

4. Assistance Games vs. RLHF

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) is the current industrial standard (e.g., used in ChatGPT), but Assistance Games offer a distinct theoretical alternative.

| Feature | RLHF (Standard Model) | Assistance Game (CIRL) |

|---|---|---|

| Human Role | Oracle/Judge: Provides labels/rewards. | Partner: Acts in the world; behavior is information. |

| Goal Knowledge | Fixed: Learned reward model is treated as ground truth. | Uncertain: AI always maintains a probability distribution over goals. |

| Incentives | Can lead to sycophancy (telling the user what they want to hear to get high reward). | Incentivizes information seeking and correction (clarifying ambiguity). |

| Safety | Relies on “patching” behavior (e.g., refusal training). | Safety (e.g., deference) emerges naturally from math (uncertainty). |

5. Critiques and Challenges

- Computational Complexity: Solving POMDPs is PSPACE-complete. While AssistanceZero shows promise, scaling this to the complexity of Large Language Models (LLMs) remains a massive engineering hurdle compared to the efficiency of RLHF.

- Human Irrationality: The framework typically assumes the human acts somewhat rationally (Boltzmann rationality). If a human acts irrationally (e.g., due to addiction or cognitive bias), the AI might learn “wrong” preferences (e.g., “the human wants to take drugs”).

- Human Modeling: To infer preferences correctly, the AI needs a robust model of human cognition ($P(action | \theta)$). We currently lack a generative model of human behavior that is precise enough for high-stakes inference.

- Manipulation: An AI optimizing for uncertain human preferences might manipulate the human to make their preferences simpler or easier to satisfy, effectively “wireheading” the human.

6. Selected Scientific References

- Core Paper:

- Hadfield-Menell, D., Russell, S. J., Abbeel, P., & Dragan, A. (2016). “Cooperative inverse reinforcement learning.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 29.

- Foundational Book:

- Russell, S. (2019). “Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control.” Viking.

- Safety Theorems (The Off-Switch):

- Hadfield-Menell, D., Dragan, A., Abbeel, P., & Russell, S. (2017). “The off-switch game.” Workshops at the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

- Reward Uncertainty:

- Hadfield-Menell, D., Milli, S., Abbeel, P., Russell, S. J., & Dragan, A. (2017). “Inverse reward design.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 30.

- Multi-Agent Extensions:

- Fickinger, A., Zhuang, S., Critch, A., Hadfield-Menell, D., & Russell, S. (2020). “Multi-Principal Assistance Games.” NeurIPS 2020 Cooperative AI Workshop.

- Recent Scaling Work:

- (Search Result Candidate) “AssistanceZero: Scalably Solving Assistance Games” (2024/2025). OpenReview/ArXiv. (Demonstrates MCTS application to CIRL).

- Generalized Efficiency:

- Malik, D., Palaniappan, M., Fisac, J. F., Hadfield-Menell, D., Russell, S., & Dragan, A. D. (2018). “An Efficient, Generalized Bellman Update For Cooperative Inverse Reinforcement Learning.” International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

Escaping the Verifier: Learning to Reason via Demonstrations

Training Large Language Models (LLMs) to reason often relies on Reinforcement Learning (RL) with task-specific verifiers. However, many real-world reasoning-intensive tasks lack verifiers, despite offering abundant expert demonstrations that remain under-utilized for reasoning-focused training. We introduce RARO (Relativistic Adversarial Reasoning Optimization) that learns strong reasoning capabilities from only expert demonstrations via Inverse Reinforcement Learning. Our method sets up an adversarial game between a policy and a relativistic critic: the policy learns to mimic expert answers, while the critic aims to identify the experts among (expert, policy) answer pairs. Both the policy and the critic are trained jointly and continuously via RL, and we identify the key stabilization techniques required for robust learning. Empirically, RARO significantly outperforms strong verifier-free baselines on all of our evaluation tasks — Countdown, DeepMath, and Poetry Writing — and enjoys the same robust scaling trends as RL with verifiers. These results demonstrate that our method effectively elicits strong reasoning performance from expert demonstrations alone, enabling robust reasoning learning even when task-specific verifiers are unavailable.